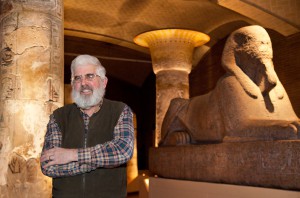

Patrick E. McGovern is the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia, where he is also an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology. In the popular imagination, he is known as the “Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, Wines, and Extreme Beverages.”

Over the past two decades, he has pioneered the exciting interdisciplinary field of Biomolecular Archaeology which is yielding whole new chapters concerning our human ancestry, medical practice, and of course what our ancient ancestors were eating and drinking. His laboratory discovered the earliest chemically attested alcoholic beverage in the world (ca. 7000 B.C. from China), the earliest grape wine (ca. 5400 B.C.) and barley beer (ca. 3500 B.C.) from the Middle East, and some of the earliest chocolate from the Americas (ca. 1400 B.C.). These findings and others have resulted in 15 international stories, and widespread public and scholarly exposure and acclaim.

He is well known for his book on Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton University, 2003/2006), and most recently, Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages (Berkeley: University of California, 2009).

Biomolecular Archaeology is the “wave of the future” in discovering the past. This supremely interdisciplinary field promises to bridge the gap between the “Two Cultures” of the humanities and the natural sciences.

Have you ever wondered what an ancient wine tasted like, or how well it paired with ancient caviar? Phrased more academically, what are the environmental and genetic factors that have shaped our species and cultures? Or what foods and beverages have contributed to our bio-cultural transformation over the past three million years?

Until recently, archaeology was limited to the inorganic remains of the past, such as pottery vessels and stone architecture. Yet human beings are mainly organic–our cuisine, our clothes, our brains, and the biosphere that we inhabit.

Revolutionary advances in chemical instrumentation over the past forty years now make it possible to answer questions about what it is to be human. We are at the beginning of a process that promises to transform our understanding of our species and yield spectacular discoveries in the 21st century.

Contact

For inquiries about Patrick McGovern’s research contact him at:

Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

3260 South Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104

(215) 898-1164

mcgovern@sas.upenn.edu

For media inquiries, please contact:

Public Information Office

pr@pennmuseum.org

(215) 898-4045

Dr. Pat

Dr. Patrick E. McGovern is the Scientific Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Project for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health at the University of Pennsylvania Museum in Philadelphia. He is also an Adjunct Professor of Anthropology. His academic background combined the physical sciences, archaeology, and history–an A.B. in Chemistry from Cornell University, graduate work in neurochemistry at the University of Rochester, and a Ph.D. in Near Eastern Archaeology and Literature from the Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Department of the University of Pennsylvania.

Over the past two decades, he has pioneered the emerging field of Molecular Archaeology. In addition to being engaged in a wide range of other archaeological chemical studies, including radiocarbon dating, cesium magnetometer surveying, colorant analysis of ancient glasses and pottery technology, his endeavors of late have focused on the organic analysis of vessel contents and dyes, particularly Royal Purple, wine, and beer. The chemical confirmation of the earliest instances of these organics–Royal Purple dating to ca. 1300-1200 B.C. and wine and beer dating to ca. 3500-3100B.C.–received wide media coverage. A 1996 article published in Nature, the international scientific journal, pushed the earliest date for wine back another 2000 years–to the Neolithic period (ca. 5400-5000B.C.).

His research–showing what Molecular Archaeology is capable of achieving—has involved reconstructing the “King Midas funerary feast” (Nature 402, Dec. 23, 1999: 863-64) and chemically confirming the earliest fermented beverage from anywhere in the world—Neolithic China, some 9000 years ago, where pottery jars were shown to contain a mixed drink of rice, honey, and grape/hawthorn tree fruit (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 101.51: 17593-98). Most recently, he and colleagues identified the earliest beverage made from cacao (chocolate) from a site in Honduras, dated to ca. 1150 B.C., and an herbal wine from Dynasty 0 in Egypt.

He is the author of Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton University Press, 2003), and most recently, Uncorking the Past: The Quest for Wine, Beer, and Other Alcoholic Beverages (Berkeley: University of California, 2009). In addition to over 100 periodical articles, McGovern has also written or edited 10 books, including The Origins and Ancient History of Wine (Gordon and Breach, 1996), Organic Contents of Ancient Vessels (MASCA, 1990), Cross-Craft and Cross-Cultural Interactions in Ceramics (American Ceramic Society, 1989), and Late Bronze Palestinian Pendants: Innovation in a Cosmopolitan Age (Sheffield, 1985). In 2000, his book on the Foreign Relations of the “Hyksos,” a scientific study of Middle Bronze pottery in the Eastern Mediterranean, was published by Archaeopress.

As a Research Associate in the Near East Section of the Museum, he has also directed the Baq`ah Valley (Jordan) Project over the past 25 years (described in a University Museum monograph, The Late Bronze and Early Iron Ages of Central Transjordan, 1986), and been involved with many other excavations throughout the Middle East as a pottery and stratigraphic consultant. A detailed study of the New Kingdom Egyptian garrison at Beth Shan, an older Museum excavation, also appeared in 1994in the Museum Monograph series, entitled The Late Bronze Egyptian Garrison at Beth Shan.

As an Adjunct Professor in the Anthropology Dept. at Penn, he teaches courses on Molecular Archaeology.

CV

Interviews and Profiles

Fall 2018: World of Fine Wine: Homo Imbibens, The Work of Patrick McGovern, by Andrew Jefford

August 2017: Brewer and Distiller International: He found the oldest-known beer on the planet…The biomolecular archaeology of ancient alcoholic beverages, by Ian Hornsey

September 2016: SOMOS TODOS CERVEJEIROS: Indiana Jones das bebidas desvenda cervejas ancestrais, by Filipe Limas

September 2016: National Geographic: Were Humans Built to Drink Alcohol? and Why I Brew Ancient Beers

August 2016: Les Cahiers Science & Vie: L’aventurier des élixirs perdus, by Betty Mamane.

May 17, 2016: edible PHILLY: Reviving Ancient Ales, by Katherine Rapin.

April, 2016: Sciences et Avenir: L’Indiana Jones de la vigne et du vin, by Rachel Mulot.

May/June 2016: Pennsylvania Gazette: Beyond the Golden Touch, by Julia M. Klein.

June 9, 2015: Scientific American Espanol: Arqueólogos resucitan bebidas alcohólicas del pueblo azteca, by Gary Stix

Jan. 28, 2015: Cinematograph: The Third Eye: McGovern and The Indiana Jones of Ancient Ales, by Virginia Campione

Jan. 8, 2015: San Francisco Wine School Insider Interview with David Furer

Dec. 12, 2014: Spektrum der Wisenschaft: Met & Co. – Alkopops bei den Nordmännern, by Annine Fuchs

Nov., 2014: All About Beer (Vol. 35, Issue 5): Beer Innovators

Nov., 2014: Malibu Magazine (Vol. 12, Issue 6): 10 x 10 Interview

Oct. 3, 2014: Financial Times of London: A Thirst for Ancient Beer and Wine, by Emma Jacobs

May 17, 2014: Harvard Political Review: To Ferment and Foment, by Olivia Zhu

April 30, 2014: Munchies: The Man Who Brings Ancient Beers to Life, by Myles Karp

Jan./Feb. 2014: The Atlantic: The Archaeology of Beer, by Wayne Curtis

Feb.-March, 2013: Philly Beer Scene, Dr. Pat and Quest for the Bygone Beers, by Patrick Ridings

May, 2012: EOS-Science: Het bier van de farao [Dutch] and La bière du roi Midas [French], by Teake Zuidema

Dec. 2011-Jan., 2012: WineMaker, Wine Archaeologist, by Wes Hagen

Dec. 1-7, 2011: Courrier international, L’aventurier de l’ivresse perdue [French translation of Dig, Drink and Be Merry, by Abigail Tucker, below]

Sept. 6, 2011: Slate Magazine, Beer Archaeologist: Tasting World History, by Christine Ziemba

Aug. 15, 2011: Newsweek (Polish ed.), Ferment Historii, by Magdalena Frender-Majewska

July-August, 2011: Smithsonian, Dig, Drink and Be Merry, by Abigail Tucker

July 25, 2011: Palate Press, Fermentation, Civilization: How History and Human Thirst Go Hand in Hand, by Emily Towe

July 5, 2011: Irish Edition (Philadelphia), Barbara Nolan: “Midas Touch–Uncorking the Past”

April/May, 2011: Mid-Atlantic Brewing News: “The Beers That Time Forgot”

April 30, 2011: Sommelier Journal, pp. 36-40, Interview by Laura Taxel

March, 2011: VINUM, Jäger des verlorenen Weins, p. 12

Jan.-Feb. 2011: Mental Floss, Golden Lobe Award for Nerdiest Beer, 10: 44

Jan./Feb., 2010: The Pennsylvania Gazette, cover story, 34-41, “Man, The Drinker,” by Trey Popp

Dec. 24, 2009, Der Spiegel, “Alcohol’s Neolithic Origins: Brewing Up a Civilization,” by Frank Thadeusz

Dec. 15, 2009 – MSNBC, Eight ancient drinks uncorked by science

July 23, 2009, NOWLebanon-“Talking To: Wine archaeologist Patrick McGovern,” by Michael Karam

2007, The World of Fine Wine, issue 18: 74-77: Before Dionysus [memorable wine], by Blake Edgar

Feb. 9, 2006, pp. 9-11: Daily Pennsylvanian, “Brewing the Past,” 34th St. feature, by S. Morse

Philadelphia Magazine, In Search of Ancient Spirits, by B. Wallace

Nov. 2005, vol. 26 (11): 54-59: Discover, “Stone Age Beer,” by Larry Gallagher

Feb. 2005: TIME Express Monthly (Taiwan), “Ch. Jiahu, with Hawthorn Accents”

Feb. 2004: TIME Asia, “The First Vintage”

2005: Populär Historia (Sweden), “Det första vinet,” by Charlotta Sjöstedt

2004: National Geographic News on-line, “First Wine?: Archaeologist Traces Drink to Stone Age,” by William Cocke.

Aug. 15, 2003: Chronicles of Higher Education 49:49: A16-A17, “Château Néolithique: Whence Wine?,” by Richard Monastersky

Nov. 7, 2003: Times Higher Education Supplement, no. 1614: 18-19: “Vintage Brews Get the Midas Touch,” as part of molecular science article

Nov. 24, 2003: Time 162(21): 60-61, “The First Vintage,” by Madeleine Nash

April 30, 2002, Wine Spectator, vol. 27(1): 133-35, “Modern Science, Ancient Wines,” by Lynn Alley

Nov. 27, 1999: New Scientist, vol. 164(2214): 54-57: “Grog of the Greeks,” by Stephanie Pain

July 31, 1996: Wine Spectator, “New Tests Find Evidence of Wine at Dawn of Civilization,” by Kim Marcus

February 21, 1983 – Chemical & Engineering News, “Special Report: Archaeological Chemistry” by Pamela Zurer

Long Bio

Photos

Click on “enlarge” icon, and double click image to view caption.

Short Bio

Support

Biomolecular Archaeology and the Museum of the Future

Over the past 25 years, the Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory has collaborated with scholars, museums, departments of antiquities, and other institutions in more than 30 countries around the world. Among others, our work has been supported by:

American Center for Wine, Food & the Arts American Philosophical Society American Research Institute in Turkey Annenberg Foundation Cornell and Harvard Universities The DuPont Co. Dupont Merck Pharmaceutical Co. European Union Fulbright Foundation Henry Luce Foundation Italian National Research Council Jerome Levy Fund Kaplan Fund Metropolitan Museum of Art National Science Foundation National Endowment for the Humanities National Geographic Society The Robert Mondavi Winery Rohm and Haas Co. Thermo Nicolet Corp. The Wine Institute

Recent research support and collaborations include the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau Laboratory, Exxon-Mobil Corp., Firmenich Inc., and the U.S. Dept. of Agriculture.

The highly interdisciplinary nature of Biomolecular Archaeology is both its strength and its weakness. It can easily fall between the cracks of more traditionally defined disciplines. Your financial assistance is thus essential in assuring that our research laboratory, the only museum-based one of its kind in the country, prospers and expands.

The museum of the future and the Penn Museum, now in the process of installing new laboratories, have much to gain from the rapidly developing field of Biomolecular Archaeology. By applying the best that modern science has to offer, we will be able to conserve our archaeological artifacts for future generations, at the same time that we answer the crucial questions of our bio-cultural origins.

As we move forward in the 21st century, we welcome your support of the Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory for Cuisine, Fermented Beverages, and Health.

Molecular Archaeology has come of age in the last 25 years. The Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, with its world-class collections, has been at the forefront of these developments. Ancient foods, perfumes, dyes, and other organics, which could only be imagined from ancient writings, can now be detected by highly sensitive instruments in the laboratory. Molecular Archaeology promises to open up whole new chapters relating to our human ancestry and genetic development, cuisine, medical practice and other crafts over the past 2 million years.

Under the leadership of Patrick E. McGovern, the Penn laboratory has developed scientific techniques for identifying ancient dyes (Royal Purple and indigo), foods, and beverages. Its innovative research led to the re-creation of the first-ever ancient feast based on the chemical evidence—the “King Midas” funerary banquet—as well as the discovery of the earliest wine and barley beer from the Near East. The laboratory reported finding the earliest alcoholic beverage in the world—a mixed beverage incorporating wild grape, rice, hawthorn, and honey from China, dating back to 7000 B.C.–as well as some of the earliest chocolate and medicinal wines.

The museum of the future and the Penn Museum in particular, now in the process of installing new laboratories, has much to gain from this rapidly developing field, the “wave of the future” in archaeology. Yet, funding for Biomolecular Archaeology falls between the cracks of the more traditionally defined disciplines. Your support is thus crucial in assuring that this research facility, the only museum-based one of its kind in the country, prospers and expands. As we move forward in the 21st century, our major needs for a Center of Biomolecular Archaeology, specially dedicated to the study of ancient wine and cuisine, are these:

| Endow new Center for Biomolecular Archaeology | $2 million |

| Endow Chief Scientist/Director’s position | $1.5 million |

| New scientific instruments: Small Gas Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (Hewlett-Packard 6890 GC with Mass Selective Detector 5973 and Data Station) | $80,000 |

| Liquid Chromatograph-Mass Spectrometer (H-P 1100 with UV detector) | $165,000 |

| Diffuse-Reflectance Infrared (Thermo-Nicolet Nexus 4700 with Centaur microscope) | $63,500 |

| Service contracts | $50,000 |

| Collaborative research | $50,000 |

| Graduate Student fellowship | $50,000 |

| Annual operating base for equipment maintenance, conference travel, collecting samples, etc. | $25,000 |

The Lab Group

A cesium magnetometer survey in 1978 located one of the largest early Iron Age burial caves ever found in Jordan. Some of the 227 excavated individuals in the tomb were adorned with pairs of iron anklets and bracelets. Our analyses showed that the metal was a mild steel, among the earliest instances of this iron-carbon alloy ever found.

The ancient pottery and glass vessel technology programs developed in the 1980’s were highly innovative at the time. We went on to tackle a long-ignored but all-important question: what did these vessels contain? A new field was pioneered that excited the scientific world and fired public imagination.

First came the chemical attestation of the earliest Royal Purple, the famous dye of the seafaring Phoenicians, demonstrating that organic compounds could survive over 3000 years.

In the early 1990’s, we announced the earliest chemically confirmed instances of grape wine and barley beer from the Near East. The laboratory then pushed back the earliest date for wine another two millennia to 5400 B.C., based on analyses of jars from the Museum’s excavation at Hajji Firuz in Iran.

In the late 1990’s, the laboratory analyzed the extraordinarily well-preserved organic residues inside the largest known Iron Age drinking-set, excavated inside the burial chamber of the Midas Tumulus at Gordion in Turkey. Our reconstruction of the “funerary feast”–which paired a mixed fermented beverage (“Midas Touch”) with a spicy, barbecued lamb and lentil stew–is the first time that an ancient meal has been re-created based solely on the chemical evidence.

Appropriately enough, “Midas Touch” has won three gold awards at major taste competitions in the past year.

Our research at the start of the new millennium has focused on the Neolithic period of ancient China’s Yellow River valley. At the site of Jiahu, we discovered the earliest alcoholic beverage in the world dating back to about 7000 B.C. It was a mixed fermented beverage of rice, honey, and grape and/or hawthorn fruit. A re-created beverage–“Chateau Jiahu”–was released in August 2006.

The research prowess of the Biomolecular Laboratory is matched by its publication record: 8 books and over 80 articles have been published in scientific journals, including a Nature cover story in its Dec. 23, 1999 issue.

Fifteen international stories have also publicized our remarkable discoveries to a wider public around the world in print media, on TV and radio, and over the internet. The laboratory’s research has been profiled in ten video programs, including a full-length feature filmed at the Midas Tumulus in Turkey. Our findings have been the focus of museum exhibits in Philadelphia, Athens, the Napa Valley, France, and elsewhere.

One can only imagine what will be excavated and analyzed in the coming years. We anticipate that many other organics–textiles, drugs, herbs and spices, even brains–will be recovered from well-preserved anoxic environments such as the deep oceans and seas, deserts, and glaciers.

Our laboratory will be called on to do the analyses, which will shed new light on the bio-cultures that have defined us as humans, including plant and animal domestication, human diet and trade, and ancient technology and innovation.

Beyond reconstructing ancient cuisine and human bio-culture by using advanced chemical techniques, a major goal of the Laboratory of Ancient Cuisine and Biomolecular Archaeology will be to “re-create” the past in its organic dimensions as never before.

New taste sensations, such as “Midas Touch” and “Chateau Jiahu,” will be one result of this experimental archaeological approach. By conjoining biomolecular archaeology with advanced artificial simulation techniques, much more of the human bio-cultural past can be “brought back to life.”

Gretchen R. Hall and Theodore Davidson, Ph.D. analytical chemists, are crucial to the research carried out by the laboratory.