I will entertain any proposal for speaking engagements, including keynotes, seminars, and short courses. In collaboration with Dogfish Head Brewery, Ancient Ales dinners profiling our re-created beverages have been a success across the country. I can either be there in person, or a film showing Sam Calagione and me tasting the beverages with paired foods can be shown. I have PowerPoint presentations for each of the lectures.

For more on the Ancient Ales dinners

Extreme Fermented Beverages

UNCORKING THE PAST: THE QUEST FOR WINE, BEER, AND EXTREME FERMENTED BEVERAGES

The history of the human species and civilization itself is, in many ways, the history of fermented beverages. Drawing upon recent archaeological discoveries, molecular and DNA sleuthing, and the texts and art of long-forgotten peoples, Patrick McGovern takes us on a fascinating odyssey back to the beginning when early humanoids probably enjoyed a wild fruit or honey wine. We follow the course of human ingenuity in domesticating plants of all kinds—particularly the grapevine in the Middle East, rice in China, and the cacao (chocolate) tree in the New World–learning how to make and preserve wines, beers, and what are sometimes called “extreme fermented beverages” that are comprised of many different ingredients. Early beverage-makers must have marveled at the seemingly miraculous process of fermentation. When they drank the beverages, they were even more amazed—they were mind-altering substances, medicines, religious symbols, and social lubricants all rolled into one. The perfect drink, it turns out, has not only been a profound force in history, but may be fundamental to the human condition itself.

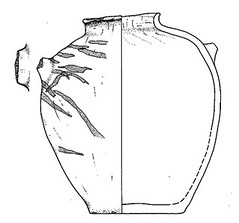

The speaker will illustrate the biomolecular archaeological approach by describing the discovery of the most ancient, chemically-attested alcoholic beverage in the world, dating back to about 7000 B.C. Based on the analyses of some of the world’s earliest pottery from Jiahu in the Yellow River valley of China, a mixed fermented beverage of rice, hawthorn fruit/grape, and honey was reconstructed. The laboratory’s most recent finding is a fermented beverage made from the fruit pod of the cacao tree, as based on analyses of ca. 1200 B.C. pottery sherds from the site of Puerto Escondido in Honduras. As the earliest chemically attested instance of chocolate in the Americas, this beverage might well have been the incentive for domesticating the cacao tree. Like grape and rice wine, chocolate “wine”—in time made only from roasted beans–went on to become the prerogative of royalty and the upper class, and a focus of religion. Some of these beverages, including the earliest alcoholic beverage from China (Chateau Jiahu), the mixed drink served at the “King Midas funerary feast (Midas Touch), and the chocolate beverage (Theobroma), have been re-created by Dogfish Head Brewery, shedding light on how our ancestors made them and providing a taste sensation and a means for us to travel back in time.

Ancient Wine

THE FIRST WINE: AN ARCHAEOCHEMICAL DETECTIVE STORY

Wine, the premier fermented beverage of Mediterranean and Near Eastern civilizations, was likely discovered and enjoyed early in human prehistory. Although the organic evidence of these unique beverages, with their special dietary benefits and psychotropic effects, has largely disappeared, highly sensitive techniques now make it possible to identify chemical compounds that are specific to wine. Our earliest finding is that the Neolithic villagers of the northern Zagros mountains of Iran were making wine and storing wine in some of the earliest pottery jars from the Middle East, ca. 5400 B.C. Terebinth tree resin was added to the wine, much like modern-day retsina, probably as a preservative and to cover up any off-tastes or odors. The pharmacopeiae of later literate societies are dominated by this resinated wine, whose origins can now be traced back to the first period of permanent human habitation.

WINES OF ANCIENT EGYPT

Before a royal winemaking industry was established in the Nile Delta, ca. 3000 B.C., the first pharaohs imported wine from the Levant, and soon developed a taste for it. During Dynasty 0, around 3150 B.C., one of the first kings of Egypt, Scorpion I, was buried in a magnificent “funerary house” in the desert at Abydos on the middle Nile River. The German Institute of Archaeology in Cairo excavated Scorpion’s tomb in all its splendor, with ivory scepter and supplies of food and drink to carry with him into the afterlife. What was most astounding was that 700 jars containing some 4500 liters of resinated wine, according to our chemical analyses, were deposited in these three rooms, which was then covered over by a roof and mound of earth.

Besides being resinated wine with terebinth tree resin to which fresh fruit (grapes and figs) had been added, the Scorpion wine had also been laced with a variety of herbs–mint, coriander and sage–according to our re-analysis of the jar residues, using state-of-the-art techniques in collaboration with the U.S. Government Tax and Trade Commission Laboratory.

We have also demonstrated that the liquid in the jars had indeed been fermented, according DNA analysis in collaboration with the University of Florence. The residues revealed fragments of wine yeast DNA, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the earliest ever recovered and the likely precursor of the bread and beer yeasts.

Once the beverage had established an economic foothold, usually being incorporated into religious ritual and social custom as well, the next logical step was to transplant the grapevine itself, and begin producing wine locally to assure a more steady supply, at a lower cost and tailored to local tastes. The Nile Delta with its extensive tracts of irrigated land, sunny days and short rainy season was ideal, and became the focus of a royal wine industry in the first two dynasties.

Soon, burials were not considered to be adequately prepared for the afterlife unless the five canonical wines from different estates in the Delta were deposited or illustrated in them. The 26 wine amphoras of the boy-king Tutankhamun that were buried with him in his famous tomb around 1330 B.C during the heyday of the New Kingdom were produced in the wineries in the Nile Delta.

Ancient Beer

Have you ever wondered what it was like to live during the heyday of the Neolithic Revolution, some 9000 year ago? More specifically, have you ever wondered what humans concocted as their earliest fermented beverages and how it tasted (and felt)? Thanks to revolutionary advances in chemical science over the past 40 years, it is now possible to tease out the ancient organic compounds that can provide us with the ancient recipe, and then re-create this beverage in the present.

This evening, Dr. Patrick McGovern of the University of Pennsylvania Museum’s Biomolecular Archaeology laboratory will discuss how his lab and colleagues have resurrected ancient fermented beverages, including the earliest barley beer (from Iran, of all places) and the recently released Chateau Jiahu from Dogfish Head Brewery, based on a 9000-year-old Chinese “recipe” of hawthorn fruit, grapes, honey, and rice malt.

Ancient Medicine

ANCIENT MEDICINAL FERMENTED BEVERAGES

Chemical analyses of ancient organics absorbed into pottery jars from Neolithic China, ca. 7000 B.C., and others from the beginning of advanced ancient Egyptian culture, ca. 3150 B.C. have revealed that a range of natural products–specifically, herbs and tree resins–were dispensed by fermented beverages. These findings provide the first chemical evidence for the earliest medicinal treatments in the world, previously only ambiguously documented in ancient medical papyri and texts. They laid the foundation for traditional medicine in these regions, and illustrate how humans around the world, probably for millions of year, have exploited their natural environments for effective plant remedies.

The active compounds have recently begun to be isolated by modern analytical techniques. My laboratory, in collaboration with colleagues at Penn’s Abramson and Medical Centers, is now testing compounds in ancient fermented beverages for their anti-cancer and other medicinal properties in a new project called “Archaeological Oncology: Digging for Drug Discovery.” Our ancient ancestors had a huge incentive in trying to find any cure they could to cure mysterious diseases and extend their life spans beyond the usual 20-30 years. Over millennia, they might well have hit upon solutions, even if they couldn’t explain it scientifically. Superstition also crept in, but in certain periods, like the Neolithic, humans were remarkably innovative in domesticating and probably discovering medicinal plants. They were lost to future generations when the cultures collapsed and disappeared, but can now be rediscovered using Biomolecular Archaeology.

Prehistoric Silk Road

ANCIENT FERMENTED BEVERAGES: EAST AND WEST ALONG THE SILK ROAD

The speaker will illustrate the Biomolecular Archaeology approach by drawing on his research on ancient barley beer and grape wine in the Near East–on one end of the Silk Road–over the past two decades, including the earliest chemically identified and published examples of these beverages from Iran ( ca. 5500 B.C.). In China–at the other end of the Silk Road–recently published evidence indicates that beverage-making using rice, fruit (grape and/or hawthorn fruit), and honey was used to make a mixed fermented beverage as early as 7000 B.C. Beyond the considerable social, religious and medical significance of this discovery, it highlights once again human innovation in using local resources to make an alcoholic drink. What is equally curious is the timing of the emergence of this beverage in China about the same time that similar beverages were being concocted in the Near East. Could it be that ideas associated with plant domestication and fermented beverage production were being transferred–however fragmentary the process and at short distances over and over again–across the expanse of Central Asia via a forerunner of the Silk Road?

Royal Purple

ROYAL PURPLE: THE DYE OF GODS AND KINGS

My interest in the Phoenicians was especially piqued when amphora fragments, covered with an intense purplish coloration on their interiors, started turning up in the 13th century B.C. levels of the Sarepta (Lebanon) excavations. At another site, such sherds might be taken as a matter of course, perhaps due to staining by a manganese ore or an exotic fungus. But when you find them at a homeland Phoenician site, thoughts turn to the celebrated Tyrian or Royal Purple dye, which was worth more than its weight in gold and became the prerogative of priests and kings.

Even the names “Canaan” and “Phoenicia” likely derive from roots meaning “red” or “purple,” underlining the importance of dyed textiles in these societies. According to Greek legend, repeated by later writers, the dye was discovered by the Tyrian high god and king, Melqart, when he and the nymph Tyros went for a stroll on the Mediterranean beach with their dog. The dog chased ahead and bit into one of the mollusks that must have once littered the shore. It came back to its master, muzzle dripping with a purple substance. The discovery was not lost on Melqart, who immediately dyed a gown with the dye and presented it to his consort.

In fact, the first foray of our laboratory into what has been called biomolecular archaeology, so-named because it focuses on ancient organic compounds, was to put the Melqart legend to the scientific test. By applying a battery of analyses, we conclusively showed that the purple color inside the Sarepta amphoras was true molluscan Royal Purple or 6,6′-dibromoindigo, the earliest yet found within the confines of a Purple dye factory..

In this lecture, I will highlight the fascinating interplay of science, history, politics and religion in cultures around the world–Phoenicia, Peru, East Asia, Mesoamerica–where related species of the purple-yielding mollusks were culled for food and their dyeing potential in textiles. Because it requires as many as 10,000 animals to produce a gram of the dye, it was also very expensive to make. In each civilization, the molluscan Purple dye eventually came to be associated only with the highest political authorities and was imbued with special religious significance. Kimonos were dyed entirely in Purple, and the extremely well-preserved textiles of the Paracas and Nazca cultures of Peru and northern Chile exhibit stunningly beautiful patterns in Purple. In 1st century Rome, Nero issued a decree that only the emperor could wear the purple–hence, the name Royal Purple.