New Evidence on Origins of Winemaking in France

New BIOMOLECULAR aRCHAEOLOGICAL Evidence

Points to the Beginnings of Viniculture in France

* * *

9,000 Year Old Ancient Near Eastern “Wine Culture,” Traveling Land and Sea,

Reaches Southern Coastal France, Via Ancient Etruscans of Italy, in 6th-5th Century BCE

PHILADELPHIA, PA June 3, 2013—France is renowned the world over as a leader in the crafts of viticulture and winemaking—but the beginnings of French viniculture have been largely unknown, until now.

PHILADELPHIA, PA June 3, 2013—France is renowned the world over as a leader in the crafts of viticulture and winemaking—but the beginnings of French viniculture have been largely unknown, until now.

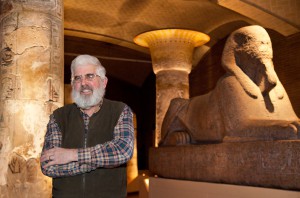

Imported ancient Etruscan amphoras and a limestone press platform, discovered at the ancient port site of Lattara in southern France, have provided the earliest known biomolecular archaeological evidence of grape wine and winemaking—and point to the beginnings of a Celtic or Gallic vinicultural industry in France circa 500-400 BCE. Details of the discovery are published as “The Beginning of Viniculture in France” in the June 3, 2013 issue of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Dr. Patrick McGovern, Director of the Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology and author of Ancient Wine: The Search for the Origins of Viniculture (Princeton University Press, 2006) is the lead author on the paper, which was researched and written in collaboration with colleagues from France and the United States.

For Dr. McGovern, much of whose career has been spent examining the archaeological data, developing the chemical analyses, and following the trail of the Eurasian grapevine (Vitis vinifera) in the wild and its domestication by humans, this confirmation of the earliest evidence of viniculture in France is a key step in understanding the ongoing development of what he calls the “wine culture” of the world—one that began in the Turkey’s Taurus Mountains, the Caucasus Mountains, and/or the Zagros Mountains of Iran about 9,000 years ago.

“France’s rise to world prominence in the wine culture has been well documented, especially since the 12th century, when the Cistercian monks determined by trial-and-error that Chardonnay and Pinot Noir were the best cultivars to grow in Burgundy,” Dr. McGovern noted. “What we haven’t had is clear chemical evidence, combined with botanical and archaeological data, showing how wine was introduced into France and initiated a native industry.

“Now we know that the ancient Etruscans lured the Gauls into the Mediterranean wine culture by importing wine into southern France. This built up a demand that could only be met by establishing a native industry, likely done by transplanting the domesticated vine from Italy, and enlisting the requisite winemaking expertise from the Etruscans.”

Combined Archaeological, Chemical, and Archaeobotanical Evidence Corroborate Discovery

At the site of Lattara, merchant quarters inside a walled settlement, circa 525-475 BCE, held numerous Etruscan amphoras, three of which were selected for analysis because they were whole, unwashed, found in an undisturbed, sealed context, and showed signs of residue on their interior bases where precipitates of liquids, such as wine, collect. Judging by their shape and other features, they could be assigned to a specific Etruscan amphora type, likely manufactured at the city of Cisra (modern Cerveteri) in central Italy during the same time period.

After sample extraction, ancient organic compounds were identified by a combination of state-of-the-art chemical techniques, including infrared spectrometry, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, solid phase microextraction, ultrahigh-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry, and one of the most sensitive techniques now available, used here for the first time to analyze ancient wine and grape samples, liquid chromatography-Orbitrap mass spectrometry.

All the samples were positive for tartaric acid/tartrate (the biomarker or fingerprint compound for the Eurasian grape and wine in the Middle East and Mediterranean), as well as compounds deriving from pine tree resin. Herbal additives to the wine were also identified, including rosemary, basil and/or thyme, which are native to central Italy where the wine was likely made. (Alcoholic beverages, in which resinous and herbal compounds are more easily put into solution, were the principle medications of antiquity.)

Nearby, an ancient pressing platform, made of limestone and dated circa 425 BCE, was discovered. Its function had previously been uncertain. Tartaric acid/tartrate was detected in the limestone, demonstrating that the installation was indeed a winepress. Masses of several thousand domesticated grape seeds, pedicels, and even skin, excavated from an earlier context near the press, further attest to its use for crushing transplanted, domesticated grapes and local wine production. Olives were extremely rare in the archaeobotanical corpus at Lattara until Roman times. This is the first clear evidence of winemaking on French soil.

The Broader Picture

For nearly two decades, Dr. McGovern has been following the story of the origin and expansion of a worldwide “wine culture”—one that has its earliest known roots in the ancient Near East, circa 7000-6000 BCE, with chemical evidence for the earliest wine at the site of Hajji Firiz in what is now northern Iran, circa 5400-5000 BCE. Special pottery types for making, storing, serving and drinking wine were all early indicators of a nascent “wine culture.”

For nearly two decades, Dr. McGovern has been following the story of the origin and expansion of a worldwide “wine culture”—one that has its earliest known roots in the ancient Near East, circa 7000-6000 BCE, with chemical evidence for the earliest wine at the site of Hajji Firiz in what is now northern Iran, circa 5400-5000 BCE. Special pottery types for making, storing, serving and drinking wine were all early indicators of a nascent “wine culture.”

Viniculture—viticulture and winemaking—gradually expanded throughout the Near East. From the beginning, promiscuous domesticated grapevines crossed with wild vines, producing new cultivars. Dr. McGovern observes a common pattern for the spreading of the new wine culture: “First entice the rulers, who could afford to import and ostentatiously consume wine. Next, foreign specialists are commissioned to transplant vines and establish local industries,” he noted. “Over time, wine spreads to the larger population, and is integrated into social and religious life.”

Wine was first imported into Egypt from the Levant by the earliest rulers there, forerunners of the pharaohs, in Dynasty 0 (circa 3150 BCE). By 3000 BCE the Nile Delta was being planted with vines by Canaanite viniculturalists. As the earliest merchant seafarers, the Canaanites were also able to take the wine culture out across the Mediterranean Sea. Biomolecular archaeological evidence attests to a locally produced, resinated wine on the island of Crete by 2200 BCE.

“As the larger Greek world was drawn into the wine culture, “ McGovern noted, “the stage was set for commercial maritime enterprises in the western Mediterranean. Greeks and the Phoenicians—the Levantine successors to the Canaanites—vied for influence by establishing colonies on islands and along the coasts of North Africa, Italy, France, and Spain. The wine culture continued to take root in foreign soil—and the story continues today.”

Where wine went, so other cultural elements eventually followed—including technologies of all kinds and social and religious customs—even where another fermented beverage made from different natural products had long held sway. In the case of Celtic Europe, grape wine displaced a hybrid drink of honey, wheat/barley, and native wild fruits (e.g., lingonberry and apple) and herbs (such as bog myrtle, yarrow, and heather).

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.