The Golden Touch of Midas

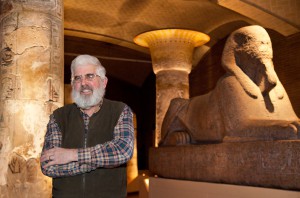

A. J. N. W. Prag of Manchester University reconstructed this plaster cast from the skull in the Midas Tumulus. (Courtesy of J. N. W. Prag, Manchester Museum, England.)

The first extreme fermented beverage that my laboratory discovered led to an exceptionally fine re-creation by Dogfish Head in 2000, namely Midas Touch. It all started with a tomb, the Midas Tumulus, in central Turkey at the ancient site of Gordion, which was excavated by the Penn Museum in 1957, over 50 years ago. The actual tomb, a hermetically sealed log chamber, was buried deep down in the center of the tumulus or mound, which was artificially constructed of an enormous accumulation of soil and stones to a height of some 150 feet. It’s the most prominent feature at the site. There was indeed a real King Midas, who ruled the kingdom of Phrygia, and either him or his father, Gordius, was buried around 740-700 B.C. in this tomb. There’s still some uncertainty, since there’s no sign announcing “Here Lies Midas or Gordius!”

When the Penn Museum excavators cut through the wall, they were brought face-to-face with an amazing sight, like Howard Carter’s first glimpse into Tutankamun’s tomb. The excavators first saw the body of a 60-65-year-old male, who had died normally. He lay on a thick pile of blue and purple-dyed textiles, the colors of royalty in the ancient Near East. In the background, you will see what really got us excited: the largest Iron Age drinking-set ever found–some 157 bronze vessels, including large vats, jugs, and drinking-bowls, that were used in the final farewell dinner outside the tomb. Like an Irish wake, the king’s popularity and successful reign were celebrated by feasting and drinking. The body was then lowered into the tomb, along with the remains of the food and drink, to sustain him for eternity or at least the last 2700 years.

All of the ideas about what our ancient ancestors were drinking–whether a wine, beer, or mead–come together in our research on the so-called King Midas funerary feast, because surprisingly all three were mixed together in the drink. The gala re-creation of the feast in 2000 was at the Penn Museum. Again based on the chemical evidence, a spicy, barbecued lamb and lentil stew, according to our chemical findings, was the entree, and it was washed down with a delicious Midas Touch. It was the first reconstruction of a burial feast based solely on the chemical evidence.

You might ask: where is the gold if this is the burial of Midas with the legendary golden touch? In fact, the bronze drinking vessels, including spectacular lion-headed and ram-headed buckets or situlae for serving the beverage, gleamed just like the precious metal, once the bronze corrosion was removed. So, a wandering Greek traveler might have caught a glimpse of this and was then inspired to concoct the legend.

But the real gold, as far as I was concerned, was what these vessels contained. And many of them still contained the remains of an ancient beverage, which was intensely yellow, just like gold. It was the easiest excavation I was ever on. Elizabeth Simpson, who has studied the marvelous wooden furniture in the tomb, asked me whether I’d be interested in doing the analysis. She didn’t have to say more. I just had to walk up two flights of stairs, and there were the residues in their original paper bags from when they were collected in 1957 and sent back to the museum. We could get going with our analysis right away.

What then did these vessels contain? Chemical analyses of the residues–teasing out the ancient molecules–provided the answer. I won’t go into all the details of our analyses, in the interests of the chemically-challenged. Briefly, by using a whole array of microchemical techniques, including infrared spectrometry, gas and liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry, we were able to identify the fingerprint or marker compounds for specific natural products.

These included tartaric acid, the finger-print compound for grapes in the Middle East, which because of yeast on the skins of some grapes will naturally ferment to wine, especially in a warm climate. The marker compounds of beeswax told us that one of the constituents was high-sugar honey, since beeswax is well-preserved and almost impossible to completely filter out during processing; honey also contains yeast that will cause it to ferment to mead. Finally, calcium oxalate or beerstone pointed to the presence of barley beer. In short, our chemical investigation of the intense yellowish residues inside the vessels showed that the beverage was a highly unusual mixture of grape wine, barley beer and honey mead.

You may cringe at the thought of mixing together wine, beer and mead, as I did originally. I was really taken aback. That’s when I got the idea to do some experimental archaeology. In essence, this means trying to replicate the ancient method by taking the clues we have and trying out various scenarios in the present. In the process, you hope to learn more about just how the ancient beverage was made. To speed things up, I also decided to have a competition among microbrewers who were attending a “Roasting and Toasting” dinner in honor of beer authority Michael Jackson (not the entertainer, but the beer and scotch maven, now sadly no longer with us) in March of 2000 at the Penn Museum.

I simply got up at the dinner, and announced to the assembled crowd that we had come up with a very intriguing beverage that we needed some enterprising brewers to try to reverse-engineer and see if it was even possible to make something drinkable from such a weird concoction of ingredients. Soon, experimental brews started arriving on my doorstep for me to taste–not a bad job, if you can get it, but not all the entries were that tasty.

Sam Calagione of Dogfish Head Brewery ultimately triumphed. Starting in 2000, Midas Touch has gone on to be the most awarded of any Dogfish brew, having garnered 3 golds medals, appropriately enough, in major tasting competitions to date, along with 5 silvers and a few bronzes tossed in for good measure. It just got another bronze at the GABF several months ago in Denver.

One footnote: the bittering agent used in Midas Touch was not hops (which was only introduced into Europe around 700 A.D.), but the most expensive spice in the world, saffron. Turkey was renowned for this spice in antiquity, and although we’ve never proven it, the intense yellowish color of the ancient residues may be due to saffron.

Fifty years ago, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology began excavations at the ancient Phrygian capital of Gordion in central Turkey. Within six years, the expedition had made one of the most spectacular archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. In the largest burial mound at the site, they located what has since been identified as the tomb of Gordion’s most famous son, King Midas. This website recreates the funerary feast of King Midas according to the archaeological excavation of the Midas Mound in Yassihöyük Turkey. Visit the Funerary Feast of King Midas website

Fifty years ago, the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology began excavations at the ancient Phrygian capital of Gordion in central Turkey. Within six years, the expedition had made one of the most spectacular archaeological discoveries of the 20th century. In the largest burial mound at the site, they located what has since been identified as the tomb of Gordion’s most famous son, King Midas. This website recreates the funerary feast of King Midas according to the archaeological excavation of the Midas Mound in Yassihöyük Turkey. Visit the Funerary Feast of King Midas website

P. E. McGovern

2000 The Funerary Banquet of “King Midas.” Expedition 42: 21-29.

P. E. McGovern, D. L. Glusker, R. A. Moreau, A. Nuñez, E. Simpson, E. D. Butrym, L. J. Exner, and E. C. Stout

1999 A Funerary Feast Fit for King Midas. Nature 402 (Dec. 23): 863-864.